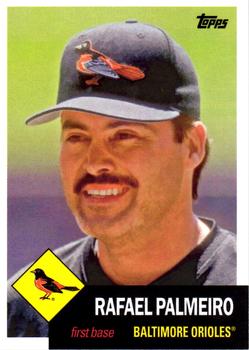

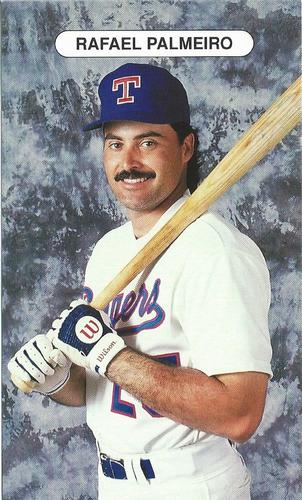

Rafael Palmeiro

When Rafael Palmeiro retired, he joined Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, and Eddie Murray as the only players to accumulate more than 3,000 hits and 500 home runs. A Hall of Fame-caliber career it was.1 But, with all Palmeiro accomplished, he is best known for wagging his finger at Congress as he denied ever having used steroids. His denial came only six weeks before he tested positive for the steroid stanozolol and threw away his chance for baseball immortality.

When Rafael Palmeiro retired, he joined Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, and Eddie Murray as the only players to accumulate more than 3,000 hits and 500 home runs. A Hall of Fame-caliber career it was.1 But, with all Palmeiro accomplished, he is best known for wagging his finger at Congress as he denied ever having used steroids. His denial came only six weeks before he tested positive for the steroid stanozolol and threw away his chance for baseball immortality.

A left-handed batter and thrower, Palmeiro played 20 seasons in the major leagues, from 1986 through 2005. He spent his first three years with the Chicago Cubs, where he mostly played left field. After he was traded to the Texas Rangers, he became a full-time first baseman, winning three consecutive Gold Gloves from 1997 through 1999. As he aged, he was also used as a designated hitter.

In the American League, Palmeiro hopped between two teams. He played with Texas for five years, the Baltimore Orioles for five years, then Texas for another five years before returning to Baltimore for the final two years of his career.

Born in Havana, Cuba, on September 24, 1964, Rafael was the third of Maria Corrales and José Palmeiro’s four sons. His brothers are José, Jr., Rick, and Andy. José, Jr. is 13 years older than Rafael, Rick, two years older, Andy, two years younger.

While Rafael’s father owned a concession stand in Cuba and made a good living, he and Maria thought America offered more opportunities. After years of trying, the family was finally allowed to leave Cuba in 1971 and settled in Miami, Florida.2 But when they left, José, Jr., 19 years old at the time, was not allowed to go because he was required to serve in the Cuban military. Although they kept in touch, it would be 21 years before the family reunited. 3

Once a fleet center fielder on a top Cuban amateur team, José would return from his job and practice baseball with his sons. “He’d come home at 4:30 every afternoon from being out in the sun working construction,” remembered Rafael, “and he’d come in, drink a glass of water, eat a sandwich and we’d go to the ballpark. That takes a lot of dedication and love.”4

José pushed the boys to improve, criticizing failure and ignoring success. “If I went 3-for-4 and struck out,” said Rafael, “he wouldn’t comment on the three hits. He would criticize the strikeout.” While his father’s method may not have been supportive, Rafael said, “[it worked] with me, because I understood what he was trying to do.”5

Rafael’s wife is the former Lynne Walden, whom he met in college. They married in December, 1985 and have two children, Preston and Patrick,6 both of whom have played minor-league baseball.

After proving his skill at Jackson High School in Miami, Palmeiro was selected by the New York Mets in the eighth round of the 1982 MLB June Amateur Draft. But when he was offered a full scholarship to Mississippi State University, he decided to go to college instead. “[The Mets] offered me $30,000 to sign,” Palmeiro said, “You can’t turn down four years of college for $30,000.”7 (In 2004, Palmeiro and his wife made the chief donation toward Mississippi State’s Palmeiro Center, a $3.8 million practice facility for baseball and football.)8

As a freshman, Palmeiro started the season with a 20-game hitting streak — the second-longest in Mississippi State history. An outfielder, he led the Bulldogs in batting average (.406) and home runs (18),9 set the school record for hits in a season (95),10 and was the only freshman selected to the Baseball America College All-America team.11

The next year Palmeiro led the Southeastern Conference (SEC) with a batting average of .415, 94 RBIs, and a record 29 home runs, becoming the first SEC player to win the Triple Crown.12 Teammate Will Clark was right behind with 93 RBIs and 28 home runs. Their 57 combined home runs were the most by teammates in SEC history13 and the duo became known as “Thunder and Lightning.”14 Although he didn’t win, Palmeiro was nominated for the Golden Spikes Award, given to the best college player in the country.15

As a junior, Palmeiro had his poorest season, batting only .300 with 20 home runs and 67 RBIs.16 Despite that, he set SEC career records for hits, home runs, and RBIs. So when he decided to enter the MLB draft at the end of the season, he was disappointed when he wasn’t chosen until the Cubs took him with the 22nd pick.

From 1985 through 1987, Palmeiro advanced through the Cubs’ minor league system and, at each stop, had a batting average over .290 and an OPS17 over .800. He spent most of September 1986 in the majors, but started the 1987 season with Triple-A Iowa. By mid-June he had earned a spot with the Cubs, finishing with a .276 BA and .879 OPS.

In 1988 he had the second-highest batting average in the National League (.307) and made the All-Star team, but hit only eight home runs in 580 at bats. As Jerome Holtzman of the Chicago Tribune wrote, “[Palmeiro’s production] would be acceptable from a slick-fielding, base-stealing middle infielder, but not from an outfielder-first baseman.”18

On December 5, 1988, the Cubs traded Palmeiro along with Drew Hall and Jamie Moyer to the Texas Rangers for Mitch Williams and five other players. Unhappy about the deal, Palmeiro said, “That’s what happens when you have [a manager and general manager] who don’t know what the hell’s going on.”19

After a mediocre first year with Texas, Palmeiro improved each of the next two seasons, leading the AL in hits (191) in 1990 and in doubles (49) in 1991. After taking two steps forward, Palmeiro took one step back in 1992. His OPS dropped 136 points and he made 25 fewer extra-base hits. In early September, the Rangers acquired the massively-muscled José Canseco, who would later call himself “the Godfather of Steroids.”

Through 1992, Palmeiro had hit 2.9 home runs per 100 at bats. In 1993, his home run rate more than doubled and he began an 11-year stretch during which he hit 37 or more home runs and drove in 100 or more runs 10 times. From 1993 through 2003, he led the AL in home runs (433) and RBIs (1266).

Through 1992, Palmeiro had hit 2.9 home runs per 100 at bats. In 1993, his home run rate more than doubled and he began an 11-year stretch during which he hit 37 or more home runs and drove in 100 or more runs 10 times. From 1993 through 2003, he led the AL in home runs (433) and RBIs (1266).

When Palmeiro became a free agent after the 1993 season, the Rangers said he asked for a six-year contract worth nearly $40 million. At that price, the team feared they would be unable to sign him and if they didn’t act quickly, would be left without a competent first baseman. On the market was Palmeiro’s former Mississippi State teammate, Will Clark, whom the Rangers swiftly signed to a five-year, $30 million deal. 20

In the aftermath, Palmeiro trashed Clark, saying, “That’s Will. That’s the way he is. He’s got no class. Friendship didn’t matter to him. He was looking out for himself. I don’t think much of Will. He’s a lowlife.”21

Palmeiro’s dislike for Clark went back to their college days. “[Our relationship] wasn’t that good.”22 He felt that Clark wanted to be the star of the team at Palmeiro’s expense. “I always pulled for him to do well. [But] I can’t say the same about him.”23

He also attacked Clark’s ability as a player. The previous season Palmeiro had hit 39 home runs and driven in 105 runs, while Clark hit 14 homers and drove in 73. “Fourteen home runs and 73 RBIs? That’s nothing,” he said.24 “Obviously, I’m the better player.”25

The next day, Palmeiro backed off, saying, “I think Will Clark is a great person and a great ballplayer. I was speaking out of frustration and I want to apologize to Will.” 26

Maybe he was also speaking out of jealousy. Clark had been drafted second, 20 picks before Palmeiro, even though it was Palmeiro who had set SEC batting records. Also, in their first eight MLB seasons, Clark had been an All-Star five times (Palmeiro twice) and finished in the top five in MVP voting four times (Palmeiro zero).

Palmeiro saved some venom for the Rangers. He called Rangers president Tom Schieffer, “a bozo”27 and “a backstabbing liar”28 and said, “[Schieffer] is very stupid when it comes to baseball.” 29 He also implied that Schieffer exhibited anti-Latino prejudice:30 “All I wanted was some respect as a player and a person. I feel like I got no respect. I think the man has something against me.”31

Palmeiro probably regretted overplaying his hand and was shocked when the Rangers forced him out. He said, “The whole idea was to build our dream house in Texas, sign, and stay there.”32 Rangers General Manager Tom Grieve said, “It evidently was very important to Rafael to stay in Texas — more important than it appeared . . . during negotiations.”33

Three weeks after the Rangers signed Clark, Palmeiro took Clark’s place in Baltimore, signing a five-year contract with the Orioles for $30.35 million.34 After hitting 23 home runs in the strike-shortened ’94 season, in each of the next four years he hit 38 or more home runs and drove in more than 100 runs, with peaks of 43 homers in 1998 and 142 RBIs in 1996 when he finished sixth in MVP voting. In 1998, the last year of his contract, he had the second-best season of his career, compiling a 6.3 WAR. The Orioles made the playoffs twice during those years, winning the Division Series, but losing in the League Championship Series — to the New York Yankees in 1996 and the Cleveland Indians in 1997.

Although it seemed Palmeiro had incinerated his bridges when he left Texas in 1993, he signed a five-year deal with them when his contract with the Orioles expired in 1998. Continuing the symmetry of their careers, Will Clark was signed by Baltimore to replace Palmeiro.

Measured by traditional statistics, Palmeiro had his best offensive season in 1999. In the first season of his return to Texas, he finished second in the AL and set career highs in home runs (47), RBIs (148), total bases (356), slugging percentage (.630), and OPS (1.050). He also placed fifth in voting for the MVP Award, the highest finish of his career. Texas won the AL West, but lost in the Division Series to the Yankees, three games to none. In Palmeiro’s other four seasons, Texas won no more than 73 games and did not qualify for the playoffs.

In 2003, the last year of his contract, Palmeiro joined Barry Bonds, Ted Williams, Hank Aaron, and Darrell Evans as the only players who hit 38 or more home runs in a season after becoming 38 years of age. But his OPS dropped below .900 for only the second time since 1993, an indication that his production was finally fading. When his Texas contract ended, Palmeiro returned to Baltimore for two years, concluding his 20-year career in 2005.

The beginning of Palmeiro’s end came when writers and fans began to suspect players of using performance enhancing drugs (PEDs). In the late 1990s and early 2000s, bloated versions of Barry Bonds, Mark McGwire, and Sammy Sosa became record-breaking home run machines. (Although MLB had banned steroids in 1991, it wasn’t until 2003 that it finally began testing players and handing out suspensions for failed tests.) In December 2003, Bonds had to testify before a grand jury in the BALCO steroids case.35 Thereafter, concern about steroid use rose to such a level that President George W. Bush condemned the drugs in his 2004 State of the Union address.36

The final shoe dropped when, in February 2005, former AL Most Valuable Player José Canseco unveiled his book, Juiced: Wild Times, Rampant ‘Roids, Smash Hits, and How Baseball Got Big. In the book, Canseco named several MLB stars who he said had used steroids; one of them was Rafael Palmeiro. Canseco claimed that when they were teammates with the Texas Rangers, he had injected Palmeiro “many times.”37

Although the book was an indictment of the sport over which he presided, Commissioner Bud Selig said he would not investigate Canseco’s allegations. Selig’s inaction prompted Congress to investigate on its own.38 Because of his appearance in Canseco’s book, Palmeiro was invited to attend the Congressional hearing on March 17, 2005. Initially he declined because March 17 is his wife’s birthday.39 Soon after, Congress’s polite invitation was replaced by a subpoena.40

When it came time for his statement, Palmeiro wagged his finger as if to scold his interrogators and said, “Let me start by telling you this: I have never used steroids, period. I do not know how to say it any more clearly than that. Never. The reference to me in Mr. Canseco’s book is absolutely false. I am against the use of steroids. I don’t think athletes should use steroids, and I don’t think our kids should use them.”41

It was not long before Palmeiro’s honesty was called into question. On May 4, he was selected under MLB policy for a random, unannounced drug test. About two weeks later, he was informed he had tested positive for the banned steroid stanozolol. (Palmeiro submitted a second sample on May 27, which tested negative for all banned substances. Injected stanozolol is detectible for about three to four weeks, taken orally, only seven to 10 days.)42 Palmeiro challenged the positive test result, contending that if there had been steroids in his body, he had no idea how they had gotten there. His grievance arbitration hearing began on June 16. 43

Several things came out in arbitration that support his claim that he never knowingly took steroids. He tested negative in 2003, 2004, and after his positive test in 2005.44 Physicians and trainers associated with the Rangers and Orioles testified they never saw Palmeiro use steroids nor had any professional reason to believe he had. One pointed out that Palmeiro never developed the pumped-up body typical of a steroid user.45

Palmeiro’s representative at the arbitration hearing argued that Palmeiro “had nothing to gain and everything to lose by using steroids in 2005.” 46 He stated that since Palmeiro was in the last year of his career, he wouldn’t have done it to enhance his future earnings nor to help recover from an injury since he had none. He also contended that Palmeiro had no personal incentive to improve his performance,47 although that point is dubious because, as the season began, Palmeiro needed 78 hits to reach 3,000.

In the part of his book in which he named Palmeiro, Canseco also mentioned Texas teammates Juan Gonzalez and Ivan Rodriguez, writing. “I sat down with Rafael Palmeiro, Juan Gonzalez, and Ivan Rodriguez, and educated them about steroids. Soon I was injecting all three of them. I personally injected each of those three guys many times, until they became familiar with how to use a needle and were able to do it by themselves.”48 In interviews with the arbitration panel, both Gonzalez and Rodriguez denied Canseco’s claims.49

Though in Palmeiro’s favor, the preceding points hardly mattered because none addressed the positive test. In his only attempt to explain how he could have taken the drug unknowingly, he advanced the notion that it may have come from taking vitamin B-12 contaminated with the steroid. 50 Palmeiro told the panel he had gotten the B-12 from teammate Miguel Tejada. But when his representatives obtained another vial of the B-12 from Tejada’s batch and had it tested, no trace was found of stanozolol or any other banned substance.51

When his representative admitted, “The Player’s Association does not contend that the B-12 shot that Mr. Palmeiro took caused his positive test result. We have no evidence to suggest that,”52 the panel ruled that he had not met “his burden of proof”53 and denied his challenge. (However, the panel made it a point to say its decision did not imply that Palmeiro had lied to them or to Congress and he was never charged with perjury.)54

Palmeiro served his 10-day suspension from August 1 through August 10. He returned to the Orioles’ lineup on August 14, but soon after missed five games due to injuries to his right knee and ankle. He came back on August 24, played five games, and went 0-for-18. In his last game, Palmeiro wore earplugs in an attempt to block out boos directed at him from opposing fans.55

On September 5, Orioles management told Palmeiro to leave the team and rehab his leg at home. Palmeiro agreed that his presence had become a distraction and said, “It was their idea . . . and I think it’s a good idea. I’ll be back. I’m not sure how long it will take, but I’ll be back.”56 He never made it.

The team’s concerns were realized soon after, when it was leaked that Palmeiro had compromised Tejada in an attempt to save himself. “I’m disappointed if that’s true,” said Orioles teammate Jay Gibbons. “I don’t think it would help to say another teammate gave you something. I think you’ve got to look in the mirror and take responsibility for your actions.”57 (Although Palmeiro had dragged Tejada into the steroid mess, Tejada did not seem to hold a grudge and publicly welcomed Palmeiro before his first game back from the suspension.)58

Palmeiro won the Silver Slugger Award twice, made the All-Star team four times, and finished in the top 20 in MVP voting 10 times. He was a consistent presence in his team’s lineup; in the 16 seasons from 1989 through 2004, he missed only 62 games, an average of fewer than four per year. He ranks 13th in home runs (563) between Harmon Killebrew and Reggie Jackson, 17th in RBIs (1835) between Ken Griffey, Jr. and Dave Winfield, and 29th in hits (3020) between Lou Brock and Wade Boggs. All these players are in the Hall of Fame.

Below are selected career totals for Palmeiro and Eddie Murray. They indicate Palmeiro was every bit as good as Murray, a first-ballot Hall of Famer.

|

AB |

R |

H |

HR |

RBI |

OPS |

OPS+ |

WAR |

|

|

Palmeiro |

10472 |

1663 |

3020 |

569 |

1835 |

.885 |

132 |

71.9 |

|

Murray |

11336 |

1627 |

3255 |

504 |

1917 |

.836 |

129 |

68.7 |

But, because of the positive steroid test, Palmeiro was seen as a cheater through the eyes of enough Hall of Fame voters to prevent him from being enshrined. Some voters have publicly expressed their disdain for steroid users:

- “Steroid users] bastardized baseball, eroded the implicit fairness of it and disadvantaged those who chose to play fairly to extents never seen before.” — Tom Verducci (si.com, January 8, 2013)59

- “I have been clear on my position on cheaters. I don’t vote for them.” — Murray Chass (murraychass.com, formerly of the New York Times, December 31, 2017)

- “If you cheated, you cheated and it’s not fair to all the players who played the game without cheating.” — Bill Madden (New York Daily News, on MLB Now, January 16, 2017)60

Many Hall of Fame members don’t want PED users inducted. In 2017 Hall of Famer and vice-chairman of the Hall, Joe Morgan, sent an email to voters in which he wrote, “Section 5 of Rules for Election states, ‘Voting shall be based on a player’s record, playing ability, integrity, sportsmanship, character, and contributions to the team(s) on which a player has played.’” Morgan continued, “. . . if a player did steroids, his integrity is suspect; he lacks sportsmanship; his character is flawed; and, whatever contribution he made to his team is now dwarfed by his selfishness.” Morgan added, “We hope the day never comes when known steroid users are voted into the Hall of Fame. They cheated. They don’t belong here.”61

In 2011, the first year Palmeiro was eligible for the Hall, he was named on 11.0 percent (75 percent needed for election) of the ballots, followed annually by 12.8, 8.8, and 4.4 percent. Because the last total was below 5 percent, his name was removed from future ballots.

Palmeiro is not alone. As of 2020, several players have been or probably will be denied membership due to the taint of PEDs. On that list are definite Hall of Famers Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens, Manny Ramirez, Alex Rodriguez, and Mark McGwire and borderline candidates Sammy Sosa and Gary Sheffield.

In 2008, he was elected to the Mississippi State University Sports Hall of Fame62 and, in 2012, to the Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame.63 On February 16, 2019, a statue of Palmeiro (and one of Will Clark) was unveiled at Mississippi State’s baseball field.64

Palmeiro never made it back to Baltimore after he was told to leave in September 2005, and no other major league team signed him. In 2018, at the age of 53, he attempted a short-lived comeback with an independent team.65 He still maintains he never intentionally took steroids and says he’s at peace with baseball and himself. “There’s a lot of other things in my life that are way more important [than the Hall of Fame].” 66 But at times, the sting of rejection remains. “I try not to think about it too much, because it hurts.”67

Last revised: January 13, 2021

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Paul Proia and Norman Macht and fact-checked by David Kritzler.

Sources

Unless otherwise noted, statistics come from baseball-reference.com.

Notes

1 Barring special circumstances, achievement of either milestone, let alone both, has meant certain membership in the Hall of Fame.

2 Ed Brandt, Rafael Palmeiro, At Home With the Baltimore Orioles (Childs, Maryland: Mitchell Lane Publishers, 1998): 125.

3 Donald Dodd, “Big League Reunion,” Clarion Ledger (Jackson, Mississippi), April 29, 1992: 1.

4 Dan Connolly, “Palmeiro’s Way: Quiet, Steady and Strong,” Baltimore Sun, July 17, 2005: A1.

5 Buster Olney, “Palmeiro’s Burning Desire Sparked On By Fiery Father,” Baltimore Sun, March 30, 1996: 1C.

6 Brandt, Rafael Palmeiro, At Home With the Baltimore Orioles, 125.

7 Barry Lasswell, “Palmeiro Has Designs for More Than Baseball,” Clarion Ledger, April 26, 1983: C1.

8 https://hailstate.com/sports/baseball Accessed July 22, 2020

9 Associated Press, “Palmeiro, Winkler Make All-America Team,” Clarion Ledger, June 4, 1983: 2C.

10 “Dawgs End Season With Hope,” The Yazoo Herald (Yazoo City, Mississippi), June 8, 1983: A7.

11 Associated Press, “NBA Fines 10 Players, Two Teams for Exhibition Games,” Clarion Ledger, July 14, 1983: 4C.

12 Armando Salguero, “Success Has Rafael Palmeiro Whistling Dixie,” The Miami News, May 24, 1985: 3B.

13 “State Enjoys Record-Breaking Year,” Enterprise Journal (McComb, Mississippi), May 31, 1984: 7.

14 Michael Bonner, “ESPN Puts Its Focus on ’85 Team,” Clarion Ledger, May 5, 2015: C1.

15 “McDowell Winner of Golden Spikes,” The Sporting News, November 19. 1984: 63.

16 Special Reports, “1985 an Unforgettable Year For Bulldogs,” Hattiesburg American, June 10, 1985: 1B.

17 OPS is short for On-base percentage Plus Slugging percentage. It has become popular because it is easy to understand and correlates well with a batter’s ability to produce runs. OPS+ indicates how much a player’s OPS is above or below average. Palmeiro’s lifetime OPS+ was 132, 32 percent above average.

18 Jerome Holtzman, “Calm Down, Palmeiro Fans, It Was Good Deal for Cubs,” Chicago Tribune, December 11, 1988: 3-6.

19 Alan Soloman, “Ranger Raffy Rips Frey and Zimmer,” The Dispatch (Moline, Illinois), December 6, 1988: C1.

20 Deene H. Freeman, “Palmeiro May Have Miscalculated Rangers,” The Kilgore News Herald, November 28, 1993: 2A.

21 Associated Press, “Will Clark: A ‘Lowlife’ or a ‘Great Person?’,” The Marshall News Messenger (Marshall, Texas), November 28, 1993: 5B.

22 https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/sports/1994/03/01/texas-still-hurts-deep-in-heart-of-palmeiro/10a3f978-b8ff-4ee7-8714-1911d20f5582/

23 https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/sports/1994/03/01/texas-still-hurts-deep-in-heart-of-palmeiro/10a3f978-b8ff-4ee7-8714-1911d20f5582/

24 “Palmeiro: Rangers Are ‘Low-Class,’ Clarks’ a ‘Lowlife’,” Tampa Bay Times, November 24, 1993: 2C.

25 “Palmeiro: Rangers Are ‘Low-Class,’ Clark’s a ‘Lowlife’.”.

26 Associated Press, “Rangers Sign Scioscia,” Tyler Morning Telegraph (Tyler, Texas), December 15, 1993: 2-4.

27 Amy Niedzielka, “Palmeiro Rips Rangers,” Miami Herald, November 24, 1993: D1.

28 Gil LeBreton, “Palmeiro’s Pouting Reeking with Greed,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, November 24, 1993: C1.

29 Tony DeMarco, “Unhappy Palmeiro Blasts Team’s Decision,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, November 23, 1993: C1.

30 Randy Galloway, “Palmeiro Deserves Credit for Engineering Reunion,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, December 3, 1998: 1D.

31 “Palmeiro: Rangers Are ‘Low-Class,’ Clarks’ a ‘Lowlife’,” Tampa Bay Times, November 24, 1993: 2C.

32 Peter Schmuck, “Palmeiro Adapts to Lonely Star State,” Baltimore Sun, March 1, 1994: C1.

33 Amy Niedzielka, “Palmeiro Rips Rangers.”

34 Associated Press, “Will Clark: A ‘Lowlife’ or a ‘Great Person?’”.

35 Rob Gloster, “Bonds Talks on BALCO,” The San Francisco Examiner, December 5, 2003: 1

36 United States Congress House of Representatives Committee on Government Reform, Investigation Into Rafael Palmeiro’s March 17, 2005 Testimony At The Committee on Government Reform’s hearing: Restoring Faith In America’s Pastime: Evaluating Major League Baseball’s Efforts To Eradicate Steroid Use: 4.

37 Jose Canseco, Juiced: Wild Times, Rampant ‘Roids, Smash Hits, and How Baseball Got Big (New York, NY: Harper Collins, 2005): 133.

38 U.S. Congress: 3.

39 U.S. Congress: 4.

40 U.S. Congress: 5.

41 U.S. Congress: 5.

42 U.S. Congress: 13.

43 U.S. Congress: 7.

44 U.S. Congress 13.

45 U.S. Congress 27-33.

46 U.S. Congress: 11.

47 U.S. Congress; 11.

48 Canseco, Juiced: 133.

49 U.S. Congress: 34.

50 U.S. Congress: 17.

51 U.S. Congress:: 9.

52 U.S. Congress: 12.

53 U.S. Congress: 12.

54 U.S. Congress: 12.

55 Roch Kubatko, “Palmeiro Covers His Ears, But O’s Can’t Plug Skid, 7-2,” Baltimore Sun, August 31, 2005: 3E.

56 Jeff Zrebiec, “Palmeiro to Rehab in Texas,” Baltimore Sun, September 6, 2005: C1.

57 Roch Kubatko and Dan Connolly, “Under Cloud of Steroids, He’ll Sit Out Season’s Final 10 Days,” Baltimore Sun, September 23, 2005: F1.

58 Dan Connolly, “Palmeiro Returns to Orioles, 10 Days Were ‘Tough Time’,” Baltimore Sun, August 12, 2005: F1.

59 https://www.si.com/mlb/2013/01/08/hall-fame-ballot-steroids-mark-mcgwire-barry-bonds-roger-clemens Accessed August 28, 2020.

60 https://www.cooperstowncred.com/hall-of-fame-conundrum-barry-bonds-roger-clemens/ Accessed September 8, 2020.

61 C. Trent Rosecrans, “Morgan: Keep Steroids out of Hall,” The Cincinnati Enquirer, November 22, 2017: 3C.

62 “Sports in Brief, Miscellaneous,” Clarion Ledger, August 20, 2008: 2C.

63 Associated Press, “Rafael Palmeiro Inducted Into Miss. Hall of Fame,” Public Opinion (Chambersburg, Pennsylvania), July 29, 2012: 6B.

64 Tyler Horka, “Palmeiro, Clark Forever Linked,” Hattiesburg American, February 17, 2019: 2C.

65 Drew Davison, “No Joke: Palmeiro Serious About Comeback,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, January 13, 2018: 1B.

66 https://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/23784220/at-age-53-rafael-palmeiro-looks-rewrite-career-end Accessed September 10, 2020.

67 https://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/mlb/columnist/bob-nightengale/2017/01/17/rafael-palmeiro-hall-of-fame-steroids-veterans-committee/96670114/ Accessed September 10, 2020.

Full Name

Rafael Palmeiro Corrales

Born

September 24, 1964 at La Habana, La Habana (Cuba)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.