As a long-time teacher and instructional coach at Crestwood Elementary School in Madison, Christine McMahon often works with students who have difficulty reading.

Some cannot sound out words. Some work so hard to decode a text that their reading becomes slow and uneven. Others have no idea what the words they’re reading even mean.

But, she said, many begin to progress once they learn through the “science of reading” or are given individualized training in small groups. It’s a practice the Madison Metropolitan School District has adopted in recent years. With this new strategy, educators are no longer teaching students to memorize what a certain word looks like or asking them to guess a word based on the picture next to it.

They show them how to form the sounds of letters with their mouths. The letter “A,” for example, most commonly sounds like “ah,” and it makes your mouth open wide and round.

Under a new Wisconsin law called Act 20, that approach will soon be used in schools statewide, departing from the “balanced literacy” method that educators have taught to students for decades and has left many children behind, according to an increasing number of critics.

“(With balanced literacy), they didn't have as deep of an understanding as to why things happened,” McMahon said. “Students thought it was a little more rote and less scientific than it truly is. They viewed reading more as rules and memorization.”

After years of stagnant reading scores, educators see renewed promise in Act 20. The law, signed in July with broad support from legislators and school districts, is set to make sweeping changes across the state in how schools teach kindergarten through third grade students how to read.

Under the act, districts next school year will need to shift to a teaching model based on the science of reading, a collection of research on how children best learn to read. It emphasizes the use of phonics and phonemic awareness, or an understanding of the individual sounds of letters and how those sounds together can form words.

Among many of its provisions, the law requires schools to assess students through reading tests. Teachers will need to complete additional instructional training, and some schools will need to change their curriculum to comply.

Natalie Holdahl, program and services director of the Madison Reading Project, and program director Deirdre Steinmetz sort through books at the book center.

What’s at stake?

A lack of reading proficiency among children is concerning to Deirdre Steinmetz, a program director for the Madison Reading Project, which provides free books to students and educators in Dane County.

By the end of third grade, children should be moving from “learning to read” to “reading to learn.” It’s widely considered a key turning point for literacy and a fundamental skill for progressing in school.

Third-graders who fail to reach their reading milestones are more likely to struggle in later grades because they cannot comprehend the written material that is key to the educational process. And those who cannot read at grade level by third grade are more likely to not finish high school, according to research from the nonprofit Annie E. Casey Foundation.

The study revealed that one in six children who are not proficient at reading in third grade do not graduate from high school on time — a rate four times greater than that of their proficient peers. The rate is even higher for third graders who score “below basic proficiency,” with around one in four dropping out or graduating late from high school, compared with 9% of those with basic reading skills and 4% of proficient readers.

Reading is not just helpful for children’s academic journeys, “it’s the foundation for life success,” Steinmetz said, from getting a job to building social and emotional skills.

Various studies have shown that adults without a high school diploma face higher unemployment rates, lower incomes, suffer worse health, are more likely to be incarcerated, and require more publicly funded social services, according to a report from the federal National Center for Education Statistics.

“Reading is everything. It’s crucial to participate in the world, so it’s important to get that process started as early as possible,” Steinmetz said. “If you don't know how to read, you can't do a whole lot.”

“It goes beyond opening a book and knowing the words,” she added. “Being literate is really important for success in life later on.”

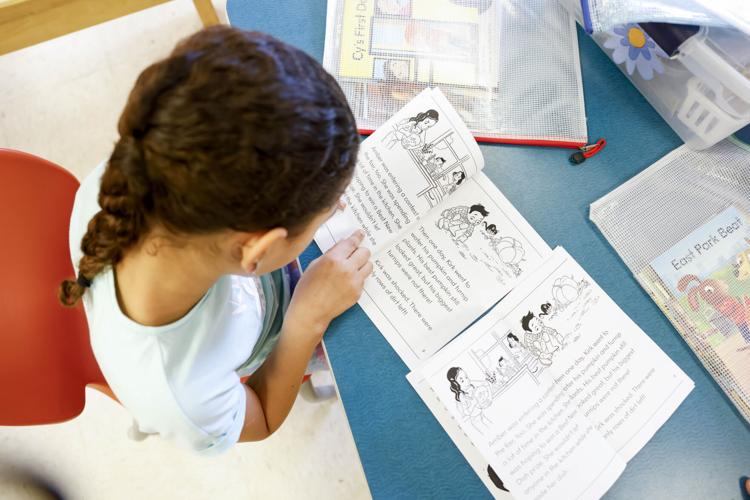

First grader Ava reads "A Turnip Mystery" at Kegonsa Elementary School in Stoughton.

Wisconsin early literacy a ‘crisis’

One of the authors of Act 20, state Sen. Duey Stroebel, R-Cedarburg, has called the state of literacy in Wisconsin a “crisis.” Results from last year’s state Forward Exam show nearly 58% of Wisconsin’s third- through eighth-graders are not proficient in English language arts.

And over a third of the state’s fourth-graders cannot read at a basic level of comprehension, according to 2022 exam results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress, also known as the Nation’s Report Card.

Last school year’s average reading score for that test was the state’s lowest since 1998, the earliest year Wisconsin’s NAEP data are available. The 2022 score dropped three points from 2019, which educators say is a result of pandemic-related learning losses.

“Teaching early reading skills remotely is really challenging,” said Laura Adams, a literacy expert and policy initiatives adviser for the state Department of Public Instruction. “When learners returned to the classroom, we definitely found that there were some gaps in their learning.

“As a state, we’re still working on closing some of those learning gaps that happened during that period of time.”

Advocates for the science of reading, however, say the reason so many kids are struggling is more straightforward: Educators haven’t been teaching them correctly.

For decades, the most popular method of teaching in the U.S. has been balanced literacy, which focuses less on phonics and instead aims to cultivate a passion for reading by ensuring students comprehend the meaning of stories. One of its strategies includes “three cueing,” which in some cases has involved prompting children to guess the meaning of words by using context clues like pictures.

As a former kindergarten and first grade teacher, Kate Ahlgren taught students to read by using balanced literacy. That’s how she and many other educators were trained, she said.

“Students were encouraged to just be exposed to reading. (Teachers thought) students learn to read by reading,” said Ahlgren, who is also director of teaching and belonging for the Stoughton Area School District. “As a teacher, I saw students struggling to read all the time, and that process is very difficult to watch.”

The problem with balanced literacy, according to science of reading proponents, is that it is not rooted in decades of reading research and evidence that points to what actually works in literacy instruction.

The research suggests teachers should focus on improving students’ fluency, vocabulary and comprehension of texts, in addition to phonics, to build their reading proficiency.

“That phonics piece, what we call foundational skills — the ability to recognize new words — if you haven’t seen that before and that foundational skill is missing, kids are inclined to struggle as they move on to more and more sophisticated texts,” said Karen Vaites, a literacy advocate based in New York. “It’s a pretty key building block.”

While a balanced literacy approach may work for some students, those from underserved communities are less likely to see success. Among Wisconsin’s fourth-graders, only 32% of Black students and 48% of Hispanic students are considered at or above basic reading comprehension, compared with 72% of white students, according to the 2022 NAEP data.

A science-of-reading method teaches students how to form the sounds of letters they see.

Wisconsin’s ‘comprehensive’ law

Wisconsin’s reading crisis mirrors declines in proficiency across the country, and its new law is part of a nationwide push for improvement.

In 2013, Mississippi became one of the first states to enact legislation on evidence-based reading instruction and phonics in schools. By 2019, Mississippi improved fourth-grade reading scores by 10 points on the NAEP exam as scores nationwide remained stagnant.

Since then, over 30 states, including Wisconsin, have implemented similar laws, and more are likely to follow suit. According to research from Esther Quintero-Corral of the nonprofit Albert Shanker Institute, lawmakers introduced 100 early-literacy bills across the country in the last year alone.

Yet Wisconsin’s Act 20 stands out to literacy advocates for its comprehensive requirements, Vaites said. The law has a long list of provisions affecting a range of people from state officials to students.

For school districts, the act deters them from buying any early literacy curriculum that uses the three cueing method. Lawmakers recently approved a list of four recommended curricula to buy, which were vetted by a new Council on Early Literacy Curricula. That council comprises six Republican appointees and three designees from the Department of Public Instruction.

While the law says it bans schools from using three cueing instruction and curricula, schools can still use this method if the “learning goal is related to vocabulary and comprehension skill building,” according to DPI. Schools also aren’t required to adopt the recommended curricula on the council’s list, but the state will subsidize a portion of the cost for those that do.

Beginning next school year, districts must additionally administer at least three literacy screening assessments each year to all kindergarten through third-grade students. Districts will then notify parents of their children’s results within 15 days of scoring the tests.

Those who score below a certain threshold will receive a “personal reading plan” to help them improve their literacy growth, and they’ll participate in intensive reading instruction throughout fourth grade until they achieve the plan’s goals. A previous version of the bill required such students to repeat all of third grade or simply third-grade reading, but lawmakers nixed it after DPI officials raised concerns and Gov. Tony Evers threatened a veto.

In college classrooms, Wisconsin-based teacher prep programs will also be required to instruct their students on how to teach reading using an evidence-based approach.

The state budget for K-12 schools includes $50 million for early literacy efforts, money that districts will use to pay for reading coaches and the approved curricula.

Griffin Granberry, Madison Reading Project book center manager, works at the front desk of the center.

DPI, educators anticipate challenges

Many schools had already begun the move toward evidence-based instruction, even before lawmakers introduced Act 20. In 2022, the Madison school district changed its curriculum to “EL Education,” which landed on the state’s approved list.

The Stoughton Area School District also changed its literacy curriculum in 2020 to “Wit and Wisdom,” another educational program now approved by the state. And in McFarland, reading interventionist Elaine Klaas said she meets with small groups of students every school day for individualized lessons, particularly working on phonics and text comprehension.

She can easily identify students who are struggling to read. They can’t automatically make out grade-level words. Their reading fluency is choppy. For some, their social and emotional growth appears hindered.

When students reach their goals, she said, she does a “happy dance.”

But Ahlgren, the Stoughton administrator, foresees challenges for schools that have not yet made the switch.

DPI spokesman Chris Bucher said the department does not have updated data on schools’ English language arts instructional materials. However, a 2021 survey, which was optional for districts to complete, showed only 27 schools were using the council’s recommended curricula. One of the four curricula the council approved was not being used in any public school at the time, according to the data.

“When you have a way of teaching that perhaps feels very comfortable, very familiar to you, and you're asked to consider something new, that's difficult,” Ahlgren said. “If you feel like you have some evidence of different types of approaches working for some students, that can be difficult to walk away from.”

“Yet our job is to provide systematic instruction,” she said. “We have the evidence to demonstrate that science-based reading is the most efficacious in terms of getting results for students.”

The science of reading is also no quick fix, said Adams, the DPI literacy expert. She said it can take three to five years for a school to see meaningful results after changing curriculum, and new research continues to roll out that will require schools to constantly evolve their instruction.

Research “also says that if it's a drastic change, then there may be an implementation dip,” she said. “It would not be surprising if in some schools or districts we saw an initial implementation dip before a strong rebound, (compared with) other school districts where the change is not as drastic.”

Within the Stoughton school district, nearly 55% of third- through eighth-graders are still considered not proficient in English language arts, compared with nearly 53% in the year prior to changing curriculum, according to state data from the Forward Exam.

“The challenges continue to be that we're still not seeing all of our students experiencing the success that we would like to see,” Ahlgren said, adding that factors such as absenteeism or a lack of connection to school can impede progress. “We've seen many students experiencing success — but not all.”

And the law to improve early literacy is only the first step, added Quintero-Corral, the Shanker Institute researcher. “How it’s implemented is what’s going to matter more,” she said. “The legislation is the roadmap, but the real work begins after that.”

Director of Curriculum & Instruction for the Stoughton Area School District, Kate Ahlgren checks in with kindergartners as they work on a geography writing lesson at Kegonsa Elementary School in Stoughton.

Changes could be costly

Another potential issue for schools is a lack of funding, Adams said. Many districts currently use federal funding to provide reading support to students. But a provision in federal law restricts local education agencies from using federal money to meet state law requirements.

“That means (districts are) going to actually need more state funding in order to provide some of those early literacy supports and interventions to learners that need them the most,” Adams said.

The Sun Prairie Area School District recently adopted new early literacy materials for its kindergarten through third-grade students, according to Bucher. The anticipated cost for the district: $1.2 million.

The professional training required for teachers and administrators to take under state law is also costly. The $50 million in state funding that legislators allocated for early literacy efforts cannot be used for teacher training. That means schools are responsible for paying for the associated costs.

The Madison school district, in particular, faces a $12.4 million budget deficit for the next fiscal year. Many other districts also are struggling to maintain their bottom line as school revenue limit increases have lagged inflation and as enrollment, which is linked to state aid, has declined statewide.

“Our school districts are working really hard to balance their budgets and identify where they can take funding away from in order to pay for some of these things, like the required reading trainings,” Adams said. “It's always a balance of needing to take money from one place in order to invest it in another, so schools are making some really hard decisions right now in order to meet those requirements.”

DPI will again advocate for additional funding in the next state budget cycle, she said, particularly for early literacy efforts and to help schools sustain changes they’ve made.

“While some of our school districts have been making moves in this direction, there are still required costs,” she said. “For those districts that are just needing to make some of these changes now, there will be a great deal of initial upfront expenses for them.”

For Dan Keyser, the Stoughton district superintendent, the initial costs have been worth it.

“It is exciting to be in our schools, watching kids who in September could look at a page and just see pictures and words, and now in April are reading those words and talking about their meanings,” he said. “I think that's fantastic.”